Early Mining on Mackay Peak

Mackay Peak (10273 ft)

Ore was first discovered in what is called the Alder Creek mining district in 1879. However the prospectors who discovered the ore were too poor to develop their claims. In 1884, additional discoveries, including one in the area of what would become the Darlington Shaft of the Empire mine, created a boom in the area.

NOTE: The Darlington Shaft (700 feet in depth) is located at the top of the the current open pit mine.

.A 50-ton smelter was built at Cliff City on Cliff Creek This smelter was build by Wayne Darlington as an experiment to see if it would be economically feasible to recover copper from the ore by smelting.

Wayne Darlington

NOTE: It could be said that Wayne Darlington was the visionary who saw the potential for the mining of copper in the Alder Creek Mining District.

The Office of State Engineer was established by the Idaho legislature in 1895. The State Engineer was responsible for regulating the use of ground water in the State of Idaho (the predecessor of today's Idaho Department of Water Resources).. Darlington was appointed by Governor William McConnell as the State Engineer and served in this position 1903 to 1904. Mr. Darlington continued operating mines in the District until the 1920's.

The smelter began operations on November 23, 1884, with the initial test run producing a pure-looking product. The smelter was closed in early December after operating a little more than a week. The smelter made another short run in 1885 but was idle by January 1886.

Darlington persuaded some New York investors to help finance his operation. After securing financing, the smelter ran from late 1890 to February 1891 Proving his theory to be profitable, Darlington sought and obtained control of the Empire Mine properties. The Empire mine, which was opened about 1884 and worked at various times, was originally organized under the laws of West Virginia as White Knob Mining Company (named after White Knob Peak [10853 ft. - the highest peak in the White Knob Mountain Range] not the town as there would be no town of White Knob for 11 years - until 1895). The smelter produced about 200,000 pounds of base copper bullion by direct smelting.

What is left of Cliff City is located at the foot of White Knob Peak at the head of Cliff Creek. To get to Cliff City, travel south on Mackay's Main Street to Smelter Avenue, cross the Big Lost River and continue up the road to the mouth of the canyon, and a major fork in the road. Take a left turn and continue in a southwesterly direction several miles until you see the Cliff Creek sign on the right hand side of the road. Follow the creek up to Cliff City.

Remnants include the wall and some metal work of the smelter, several cabins, and charcoal kiln (located below Cliff City, down the creek a ways) for making charcoal for the smelter.

Ausich Family Cabin (Restored) Located above Cliff City

The Wall (footings for the 50 Ton Smelter Building) is Situated on the Leveled Ground Hiding in the Trees across the Middle of this Picture. Part of the Smelter Furnace is in the Foreground

Close Up of One End of the Wall. Notice, It is all Rock with no Concrete to Hold the Rocks in Place, Wall was Build Prior to 1884

In the 1880's there were no Such Things as Welders. Large Pieces of Equipment had to be Riveted Together. Small Items could be Forge Welded using Borax and a Hammer to Pound Pieces of Metal Together

NOTE: Electric Welders were not common until the 1930's

There are Other Large Pieces of the Smelter Scattered around the Site

Cliff Creek Area Scenery

With the success of the Cliff Creek smelter, Darlington wanted to build a 600 ton capacity smelter. In order to accomplish this task he had to raise a large amount of money. He sought the backing of a wealthy financier who had been one of the four members asssociated with the Comstock Silver mines in Nevada. This man's name was John William Mackay. Darlington, the Mining Engineer and Superintendent, became General

Manager of White Knob Mining Company.

NOTE: Darlington had been operating mines on the foothills of Mackay Peak for over 15 years before involving J.W. Mackay in his operations. Contrary to what many locals believe Darlington got Mackay to fund his mining operations. Mackay did not bring Darlington to run his mines.

John William Mackay

John William Mackay

The property of the Empire Copper Company, the largest producer of copper in the state of Idaho, is located on a steep mountain side 3 1/2 miles southwest of the city of Mackay in Custer County. At the height of its production it consisted of 38 mining claims, a smelter capable of handling over 500 tons of ore daily, and a 7-1/2 mile narrow gauge railroad connecting the mines and smelter.

The 600 ton capacity smelter was begun some time in 1898/9 and was about half completed when John William Mackay died in London at the age of 70 due to heart failure in 1902. Mackay's death put control of the White Knob Mining Company in the hands of the remaining financiers;' most of whom were opposed to Darlington's plans for the smelter.

NOTE: Clarence Hungerford Mackay (son of John William Mackay) is not mentioned by name in any of the sources listed in the Bibliography. Any articles listing Clarence Mackay as having any direct involvement in the Empire Mine may be in error. Articles listing Clarence as the namesake of the City of Mackay Idaho, appear to be incorrect at well. All articles I found indicate that Wayne Darlington named the City of Mackay after his benefactor John and not John's son Clarence.

Darlington's plans for the smelter were changed and the smelter was not completed at this time. Those in control of the funding converted the smelter into a matte plant. The matte plant would use sulfur to create a copper sulfur matte that was cheaper to produce.

Darlington resigned as General Manager of White Knob Mining Company, and in the hands of high priced operators and with insufficient sulfur in the ore, the matte plant proved to be very unsuccessful.

NOTE: "Mr. Wayne Darlington, one of the most successful and experienced mining engineers in America, was for five years in charge of John William Mackay's mining properties." (Harper's Weekly -1907) This article about Wayne Darlington was published circa 5 years after Mackay's death.

The financiers turned the matte plant over to an operator from California by the name of Frank Leland. Leland had orders to junk the matte plant and close operations of the mining company. Leland discovered he had several thousand tons of low-grade ore on hand and thought he could use one of the smelters big furnaces to process the ore.

Leland sold off unneeded equipment and supplies and put the company assayer in charge of the smelter operations. He leased the mine to experienced mine operators; who, went to work mining high-grade ore to supplement the low grade ore on hand. This lead to the smelter operating the one large furnace for several months producing 25 carload shipments of high-grade gold and silver-bearing copper matte, The resulting furnace slag contained less than one-half of one percent copper. The smelter was shut down in the fall of 1905. Because of the success of the mine lease system, Leland continued leasing properties and at the time about 100 men were employed on the hill.

Ore from the Darlington Shaft was brought to the loading bins at the 700 foot level by the Weiler Tram.

Weiler Tram

Darlington Tunnel is located in extreme upper left of the picture above. The loading bins for the trains at the 700 foot level are in the lower right. The Weiler Tram is the line running from upper left to lower right. The Weiler Tram was the gravity tram which brought the ore from the Darlington Tunnel to the ore bins used to load the electric trains which hauled the ore down the mountain to the smelter located on the Big Lost River.

Picture to Come

Darlington Tunnel Today

Bottom of Weiler Tram at the 700 Ft. Level

The picture below was taken looking down the Weiler Tram at the 700 foot level. The Alberta Tunnel, constructed to connect with the bottom of the Darlington Shaft was completed circa 1905. With the completion of the Alberta Tunnel the Darlington Shaft was no longer used and the Weiler Tram was abandoned The 700 foot level was nicknamed the Alberta Level and because other adits (tunnels to follow ore veins, explore and or remove ore) were established from the Alberta Tunnel, it also became known as the Main Level.

Notice the tram track between the buildings. This was for the horse drawn tram to move the ore from the end of the Weiler Tram to the beginning of the tram going to the chute and into the ore bins.

Notice the tram track between the buildings. This was for the horse drawn tram to move the ore from the end of the Weiler Tram to the beginning of the tram going to the chute and into the ore bins.

Looking Down Weiler Tram at Loading Chute and Loading Bins

Horse Pulling Empty Ore Cars on Tram from Ore Bins at 700 Ft. Level

Alberta Tunnel Today

Horse Tram and Loading Chute at 700 Ft. Level -

Buildings of White Knob (1902) in Background

The picture above shows part of the tram which had the horse pulling the ore cars from the loading bin in the picture before this one. This picture shows the lower end of the town of White Knob. The main part of the town is located out of the picture going up the hill. White Knob was established circa 1895. Miners from Cliff City and White Knob lived there to save travel time from other towns located at the foot of the mountain such as Houston, Alder City and Carbondale; as the miners for the most part had to walk to work.

NOTE: The above picture of White Knob is believed to be taken after 1917/18. Peaking over the ridge between the two trees is the top of the loading bins for the Aerial Tram which started operation about 1918.

The ore was hauled from the bins to the smelter along a narrow gauge railroad track. The track was about 7-1/2 miles in length. A narrow gauge was selected because it allows for sharper curves which is a plus when building a railroad in steep mountain terrain.

A standard railroad gauge, or the distance between the rails is 4 ft. 8-1/2 inches. Coincidentally the same distance as the space between the wheels of the covered wagons used by the pioneers who crossed America coming west (maybe not a coincidence, since the wagon drivers would try to find the best routes just as the railroad builders did). Narrow gauge goes from the standard gauge down to a 12 inch gauge. The gauge of the railroad going up the hill was 24 inches.

A standard railroad gauge, or the distance between the rails is 4 ft. 8-1/2 inches. Coincidentally the same distance as the space between the wheels of the covered wagons used by the pioneers who crossed America coming west (maybe not a coincidence, since the wagon drivers would try to find the best routes just as the railroad builders did). Narrow gauge goes from the standard gauge down to a 12 inch gauge. The gauge of the railroad going up the hill was 24 inches.

The first engines to pull oar cars up and down the rails were electric engines nicknamed "Jack," and "Betty" Electricity was generated at the700 ft. level up hill from the loading bins. These engines were in operation from about 1901/2 until Frank Leland replaced them with the Shay Steam Locomotives in 1905 as part of his reorganization and revitalization. Leland believed the Shay would be able to transport the ore to the smelter at 1/4th the cost of Jack and Betty.

Electric Engine and Cars Loading at Ore Bins (1903)

The rise in elevation from the smelter on the Big Lost River to the loading bins at the 700 foot level is 2,000 feet. This was accomplished in 7-1/2 miles of curves, graded crossings and the famous trestle.

Electric Train and Cars Loaded with Miners Crossing Trestle

Close up of "Jack"

Shaw Engine Used on the Hill Starting in 1905

The Shay engine was invented by Ephraim Shay to enable him to haul logs in the Oregon winters. The steam boiler is connected to an engine with usually 2 or 3 vertical pistons. The pistons of the engine turn a crank shaft rather the the large rear wheels of a conventional steam engine. The crank shaft has gears which match the gears on each of the four drive axles. This gives the Shay eight drive wheels that provide more power and traction for pulling heavy loads up steep grades.

Steam Engine Pistons Connected to Crank/Drive Shaft

Drive Shaft Gears Connecting to Wheel Gears

Shay Engine and Crew on Grade (1915)

View of Present Day Mackay from Railroad Bed on Hill

Shay Pushing Cars Across Trestle

Trestle Today (Restored)

Crossing the Trestle

NOTE: Today the Rail Road Bed is part of the Mine Hill ATV Trail. It begins on the main road going to Cliff Creek, goes past the Alberta Level, under the Head House, past the Bullion Tunnel, down the Main Street of the White Knob Ghost Town and back onto the main road going back to Mackay. The trail can be ridden in either direction. The actual Rail Road Bed goes between the Alberta Level and the Cliff Creek road and is limited to 50 inch ATVs ONLY.

Shay Engine With Ore Cars Going to Ore Bins

Shay Coming in to Ore Bins

Taking on Water at the Smelter

NOTE: Water for the engines was piped down from Cliff Creek

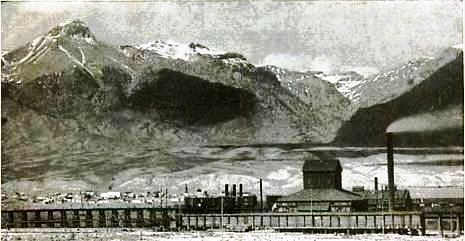

600 Ton Smelter on Hill Above Big Lost River

600 Ton Smelter (circa 1924)

The picture above shows the construction of a large structure in the center. This structure would contain the concentrating mill. Rather than recover the copper from the raw ore by smelting or matting, a concentrating mill was constructed to concentrate the copper containing material using chemicals. The building to the center right of the picture, the one with the large smoke stack was the blacksmith shop. This building is used today to house the Hard Rock Mining Exhibit.

NOTE: The tailings from the concentrate mill were stored in a pond located some distance to the right of the smelter. For years the kids of Mackay played in the dried tailings until they were recently covered by the private owner as a recovery and restoration project. We called the place the "Clay Mines."

The romantic era of the Shay Locomotive lasted from about 1905 to 1918. A three mile aerial tramway replaced the 7 1/2 mile Shay railroad. The aerial tram was constructed in 1917 and 1918 at a cost of $125,000.

Head House

Ore was brought to the head house from a tunnel, then into the covered tram which lead to the large ore bins. The covered tram not only saved the miners from shoveling snow from the tracks, but also protected those traveling on the main road between White Knob and the Empire Mine and associated facilities from falling objects.

Head House Today

The aerial tram carried full ore buckets from the loading bin at the head house to the unloading bins at the smelter, a distance of 3 miles. The tram consisted of 36 towers supporting 4 wire ropes and a tensioning tower located at the tram midpoint. A 1-1/4 inch diameter wire rope on each side of the tower supported the buckets as they traveled up and down the cable. Loaded with ore going down to the smelter on one side; and, either empty or loaded with coal, supplies, men (?) going back up the mountain to the head house on the other side. This large wire rope was a continuous stationary rope about 3 miles long.

The aerial tram was powered using a free power source, gravity. The weight of the loaded ore buckets were pulled by gravity down the supporting wire rope. To control the decent and to use this energy to pull the empty buckets back for another load, another wire rope was used as the power rope. This power rope was constantly in motion. Each ore bucket had a clamping device which when closed tighten the clamp to the rope thus securing the bucket to the rope. To load or unload a bucket, the operator pulled a lever releasing the clamp, allowing the rope to continue to move through the clamp; the bucket being stopped momentarily to load or unload. Once the process was completed, the operator pulled the lever securing the clamp to the rope allowing it to continue on its way. Timing was very important. This was a dangerous operation and at least one operator was killed when unloading a bucket at the smelter bins when he was caught between an incoming bucket and the side of the heavy bin.

NOTE: I went to school with the son of the man who was killed. He still has relatives living in Mackay.

Tensioning Tower

The tensioning tower was located in the middle of the aerial tram run. As buckets moved up and down the support wire rope, differences in weight, temperature, and continued use caused the wire rope to either shrink or stretch in length. The tension on the support rope had to be maintained in order for the tram to operate correctly. To adjust the tension, buckets were filled with large rocks which were attached to devices on the support rope to reduce or increase the tension of the rope by adding or removing rocks. Notice the spacing of the ore buckets seen on the wire rope to the left of the tower.

Buckets Traveling on the Aerial Tram

The large 1-1/4 inch wire rope can be seen under the pulleys on the bucket support structure. The power wire rope is the lower rope. The clamp device can be seen on this rope. Notice the two buckets passing through the tower; one coming to the Smelter the other going to the Head House.

Close up of Ore Bucket and Clamp

Unloading Station and Bin at Smelter

NOTE: The term wire rope is used to describe the rope used on the aerial tram. Like any other rope which is made of cotton, hemp, rawhide, plastic strands twisted or braided together to form the rope; the wire rope is made the same way only the strands are made of steel wire. The term "cable" is correctly used to refer to electrical wire.

Bullion Tunnel

The Bullion Tunnel was located at the southend of the Town of White Knob. The tunnel is located to the right center of the above picture. Tracks lead from the the tunnel entrance to the loading bin in the center of the picture. Tracks from the loading bin tram the ore to the loading bin at the Alberta Level. The grade formerly used by the tram to the Alberta Level is now a part of the Mine Hill ATV Trail.

NOTE: My friend, Joe Ausich, lived in the area at this time. He told me that the first White Knob School House was located across the road from the Bullion Tunnel which would be out of the above picture to the lower right. During Christmas Vacation (don't remember year), Joe said a snow slide wiped out the school house and the entire complex shown in the right hand side of the picture. Neither were ever rebuilt. The mother's insisted that a new school house be built one canyon to the west of the town.

Picture to Come

Cossak Tunnel and Crew

The Cossak Tunnel is located at the 1,600 foot level. Originally named the Van-Austin Tunnel but later dubbed the

Cossack. This tunnel was begun in 1903 to intersect the ore bodies believed to

continue beneath the Alberta Tunnel, at the 700 foot level.

Development on the Cossack steadily continued. In 1912 the tunnel was 1,000

feet in length; 2,000 feet in 1913; 4,500 feet in 1915; 5,500 in 1922; and it

obtained its maximum length of 6,000 feet by 1930. The ore zone, originally

projected to intersect at 2,500 feet from the portal, was finally reached at 4,500

feet. Ore was taken out through the Alberta Tunnel.

Hard Rock Miners with Drill

Cossak Compressor Building and Coal Bin

The Compressor building was used to generate steam, and compressed air, for the Empire Mine properties. The building at the right at the end of the Compressor Building is a coal bin. Coal to feed the boilers in the building was brought to the bin bu ore cars on the aerial tram coming back to the head house to reload. The structure at the top is to unload the bucket.

Cossak Tunnel and Compressor Building Today

The Empire mine was by far the largest producer in the area at one time consisting of 38 mines, but other mines with significant production include the Homestead, Horseshoe, Doughboy, Blue Bird, and Champion mines. There are no production records prior to 1902. Production records from 1902 to 1979 show that the six top mines in the area produced a combined total of 994,269 tons of ore. From this ore was obtained 41,997 ounces of gold, 1,774,889 ounces of silver, 62,234,080 pounds of copper, 15,101,855 pounds of lead, and 5,496,067 pounds of Zinc.

Horse Shoe Mine Crew

Remains of Winch Tower Covering Open Shaft

The open shaft pictured above is located just east of the Main Street of the Ghost Town of White Knob. This shaft is unprotected and should be approached with caution! The ground surrounding the opening is unstable.

Personal conversations with friends who were born/raised in Cliff City and White Knob including:

Ivan Taylor (Taylor Family Sawmill), Joe Ausich (Ausich Family Cabin), Don and Ken Anderson (Anderson Cabin), Harold Whitney, and Clint Whitney.

Alder Creek Mining District Preliminary Assessment and Site Investigation, Idaho Department of Environmental Quality December 2005

Descriptive inventory of the papers of the Empire Copper Company in the University of Idaho Library prepared by Judith Nielsen in February 1982 which included:

Ivan Taylor (Taylor Family Sawmill), Joe Ausich (Ausich Family Cabin), Don and Ken Anderson (Anderson Cabin), Harold Whitney, and Clint Whitney.

Alder Creek Mining District Preliminary Assessment and Site Investigation, Idaho Department of Environmental Quality December 2005

Descriptive inventory of the papers of the Empire Copper Company in the University of Idaho Library prepared by Judith Nielsen in February 1982 which included:

The Copper Handbook. Compiled and published by Horace J. Stevens. Houghton, Michigan. 1903, 1909

Idaho. Inspector of Mines. Annual Report. 1901-1974

Leland, Frank Milton. Letters contained in the Empire Copper Company papers.

Mackay Miner (newspaper) various issues.

The Mines Handbook. New York, H.W. Weed. 1916, 1918, 1926, 1931

Mines Register. New York, Atlas Publishing Company. 1937, 1940, 1942, 1946, 1949, 1952, 1956.

Umpleby, Joseph B. Geology and ore deposits of the Mackay Region, Idaho. Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office, 1917.

Pictures are from the collections of Judy and Jani Malkaweicz, Don and Charlotte McKelvey, Barbara Chaffin, and my (Wayne C. Olsen) collections. Thanks for sharing

Comments

Post a Comment